For many energy communities (ECs), adopting energy solidarity practices to tackle energy poverty is new territory. In Session 2 of the latest CEES webinar series, Partners speak openly about the experience of collaborating with others to engage with vulnerable households. And behaviour change expert, Dr Sea Rotmann, bring international perspectives.

The European Green New Deal identifies ECs as critical to both the just clean energy transition and to tackling energy poverty. But most ECs find this role is bigger and more complex than they first anticipate. Often, they find it particularly challenging to a) identify ‘who’ is facing energy poverty and b) engage with them in meaningful ways (as discussed in Session 1 of this webinar series).

In this second webinar, three CEES Partners present on how they sought to improve their reach and impact by identifying and engaging with ‘middle actors’ — i.e. other entities that already had close connections with vulnerable households and could facilitate introductions.

ECs should not feel discouraged, according to Invited Presenter Dr. Sea Rotmann. Years of research on ‘how to reach the hard-to-reach’ (HTR) shows that policy makers, energy companies and other actors the world over have mostly failed to engage in meaningful ways. Thankfully, that research also reveals better approaches.

Keep reading for a short recap or use the link to watch the full webinar. The time at which each presentation starts is indicated as [XX:XX].

CEES Partners featured

ALIenergy [07:37]

After first probing the question, ‘Why people don’t ask for help?’, ALIenergy sought to identify champions that could help spread the message that support and services are available. In turn, they trained frontline workers at such agencies on how to spot signs of energy poverty. Managing expectations emerged as an important element, both among partners and in terms of what each partner could do for people in vulnerable situations.

Coopernico [17:30]

Coopernico raised the challenge of finding oneself in an ‘intermediary dilemma’, when trying to connect with people living in energy poverty. Initially, they found immense value in collaborating with local stakeholders that have strong relations with particular social groups. To attract people to ‘energy cafe’ events, for example, they joined forces with ‘senior universities’. While attendance was high, the events missed the mark on the target audience Coopernico most wanted to reach. The arrangement also created barriers to further engagement, as privacy agreements meant the co-hosts could not share the contact information of attendees. The takeaway is to ensure partners have shared goals and agree up front on processes that will facilitate reaching them.

Repowering London [26:30]

Repowering London works in low-income and highly diverse areas of London. As such, it finds it critically important to work closely with ‘community leads’ who are already well-trusted by specific segments of the population. These community leads have language skills and cultural/social knowledge that supports a deeper level of engagement. Committed to making these roles paid, part-time positions, Repowering London can also demonstrate that is actively supporting local employment and capacity building.

Invited Presenter: Dr. Sea Rotmann: Reaching the ‘hard-to-reach’ [56:30]

Recapping several years of international research on successful — and more often failed — efforts to connect with people in energy poverty, Dr. Sea Rotmann, quickly acknowledged a valid criticism of the term ‘hard-to-reach.’

“We shouldn’t put the onus on the individuals in energy poverty to come find help. We need to find out what it takes to bring help to them,” said Dr. Rotmann, a behaviour change expert and social ecologist from Aotearoa, New Zealand.

Ultimately, this investigation (led by the International Energy Agency) found that most ‘campaigns’ by governments, energy companies and even civil society organisations fail for two main reasons. First, governments and energy companies already suffer a massive ‘trust deficit’ among the most vulnerable people. Second, the methods and messages these campaigns tend to produce are irrelevant to people in need.

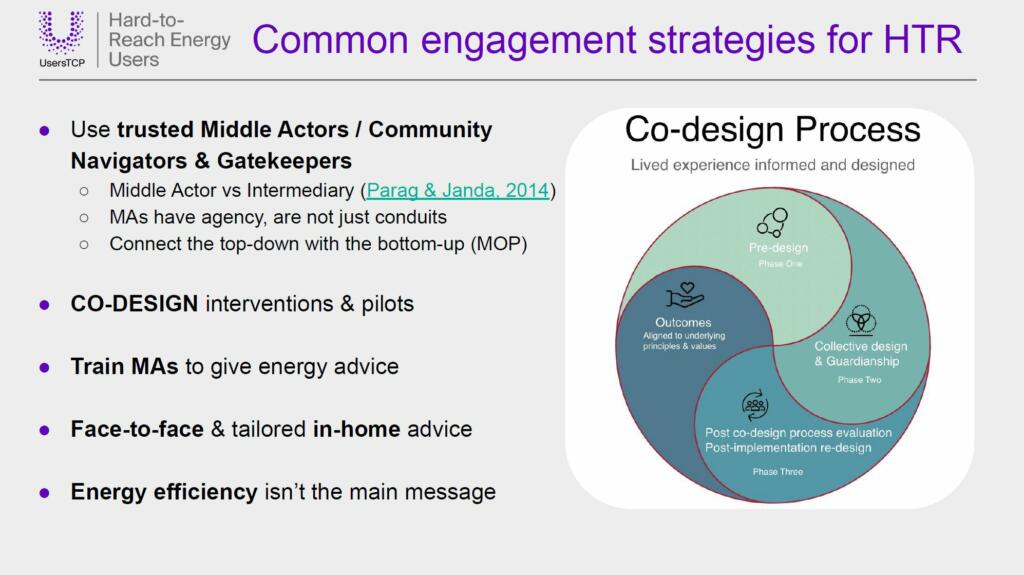

Inviting affected people to participate in ‘co-design’ of communications campaigns and engaging ‘middle actors’ in spreading the message can be game-changers, says Dr. Rotmann.

Co-design centres on recognising the enormous value of reaching out to ‘experts who bring the lived experience to the table‘ to better understand their needs and frustrations, as well as what messages will resonate with them and what actions will be most relevant. Importantly, it also creates opportunity to probe the reality that, for many individuals and households in vulnerable situations, there are no ‘quick fixes’. Often, current energy hardships reflect intergenerational trauma and multidimensional poverty.

And that reality reinforces the need to engage with a wide range or ‘middle actors’, from local civil society organisations (CSOs) and municipalities to national policy makers and energy companies, regulators or ombudspersons. Increasingly, depending on whether such actors enable or hinder engagement with the affected communities, Dr. Rotmann notes that (in the New Zealand context) practitioners tend to apply the terms ‘community navigators’ or ‘gatekeepers’. Not surprisingly, gatekeepers tend to try to control what information reaches who, whereas community navigators seek to learn what information and interventions are needed by people at the heart of this crisis. And to use that knowledge to help determine which actors can respond most appropriately.

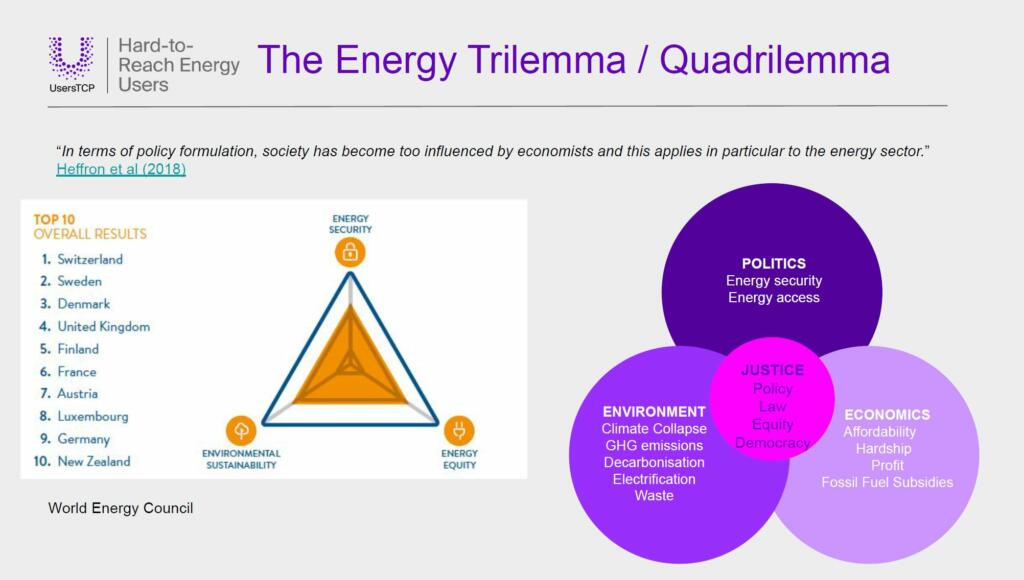

Acknowledging that energy policy is complex, Dr. Rotmann suggests it has for too long been viewed as an ‘energy trilemma’ that requires a constant balancing of energy security (which is linked to access), equity (associated with both affordability and profits), and environmental sustainability. To date, she and others believe that have energy policy has been pulled too much towards the economic corner, usually at the expense of energy justice. Achieving a just, clean energy transition, she says, requires shifting to consider a ‘quadrilemma that puts energy justice at the core of all decisions‘.

With such factors in mind, the government of New Zealand and other actors recently shifted the way they speak about the situation and how they will tackle it. Now, the aim is to ensure that all citizens enjoy ‘energy well-being’ while acknowledging that many are somewhere on the spectrum between that goal and its opposite ‘energy hardship’. This helps better pinpoint who needs what interventions.

When trying to reach people who do not ask for help or do not get or accept invitations to events that aim to offer support, Dr. Rotmann suggests that combining co-design with engagement of trusted middle actors can be vital to giving agency — meaning the ability to take action or to choose what action to take — to households affected by energy injustices.

Click below for summaries of other webinars in this series:

- No 1: Connecting with vulnerable households

- No 3: Practical ways to make a difference

- No 4: Creating an ecosystem for sustained action

Interested in re-posting these webinars to reach your own networks? Drop us a line: marilyn.smith [@] energysolidarity.eu