Knowledge about energy can empower households to better manage consumption, reduce energy-related emissions and lessen the burden of energy poverty. Knowing when and how to boost ‘energy know-how’ or apply ‘energy literacy’ – or use both in combination – can influence the success of projects and programmes.

So, what’s the difference and why does it matter?

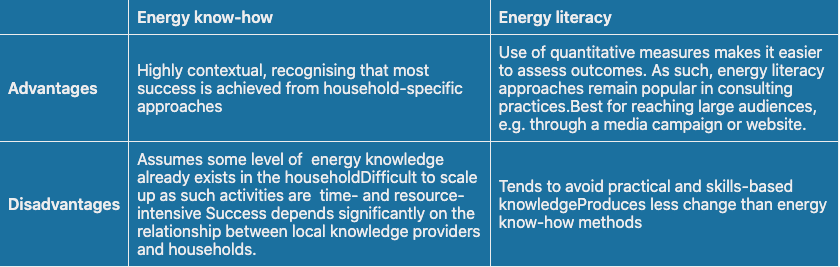

Promoting behavioural change can be an important tactic in tackling energy demand and energy poverty. Understanding the strengths (and weaknesses) of two approaches – energy know-how and energy literacy – can help determine when to apply which, according to Kevin Burchell, University of Birmingham (CEES project partner).

Energy literacy approaches, says Burchell, emphasise factual knowledge about energy, energy systems, carbon dioxide (CO2), climate change and personal energy consumption. Often, policy recommendations apply this approach, essentially aiming to tackle energy demand and energy poverty through standardised education and communications. Websites that show energy consumption patterns and offer saving tips are a typical example. While it relies on cognitive reasoning, this approach often reflects a set of ‘ideal’ attitudes and behaviours.

In contrast, energy know-how approaches prioritise practical skills, experience and guidance that is tailored to the householder’s specific situation. Energy know-how can be enhanced through social and community-based activities, such as:

- in-home energy audits

- open house demonstrations

- thermal imaging events

- and any other way of providing householders with tailored advice on how to improve efficiency or adapt habits.

In the Smart Communities action research project, Burchell and his colleagues investigated the characteristics of knowledge that are valuable and actionable for householders, as well as the practical activities through which they acquire such knowledge. Their results show that, depending on ‘who’ is aiming to do ‘what’, both approaches have merit.

Energy literacy raises awareness and supports data collection, but falls short in delivering change

Energy literacy, according to Burchell, primarily uses quantitative methods (e.g. surveys) to assess current knowledge. It often draws on behavioural models deriving from educational and social psychology and may be paired with educational campaigns.

Energy poverty policies tend to lean towards this approach for its relative ease of application. In the UK, for example, the government regularly uses it to assess consumer knowledge – e.g. whether people are aware of their electricity consumption in kilowatt hours (kWhs).

A policy action linked to such quantitative data might be the roll-out of smart metres, based on the argument that if people can ‘see’ how much they consume, they are more likely to take steps to reduce it. Some campaigns go a step further by providing comparative data from similar houses, creating a degree of ‘peer pressure’ to promote efforts to reduce consumption.

The upside of energy literacy practices is that they can reach large audiences for relatively low cost per person or household. But as the end result is usually ‘static measures’, Burchell argues that they have relatively low impact in actually reducing energy consumption or tackling energy poverty.

Energy know-how prompts change at the household level, but is resource-intensive

Prioritising practical knowledge and the skills necessary to trigger change within a household, energy know-how typically involves more qualitative methods. With experience and practice recognised as playing key roles in boosting know-how, demonstration houses and home visits – to ‘show and tell’ specific energy-saving measures – are common examples. Know-how approaches tend to rely on sociological, ethnographic and anthropological theory and concepts, thereby ‘making space’ for the vast diversity of communities and individual households.

Importantly, behavioural change requires knowledge of the specific material objects involved in executing energy saving measures. Householders and building owners, for example, must understand (to some degree) the infrastructure of the home or building: What kind of boiler does it have? What type of windows? What materials are needed to improve living conditions (e.g. insulation)? Then, they need to learn what measures they could take to achieve greater thermal comfort for lower energy consumption, within their specific context.

Energy know-how also focuses on individual energy behaviours, assessing whether occupants can ‘tweak’ habits that carry high energy costs. This might include switching off power bars at night to avoid the ‘vampire’ consumption of electronic devices that are on ‘stand-by’ 24/7, even if rarely used.

Ultimately, uptake of skills acquired through energy know-how is closely linked to the level of trustworthiness that householders ascribe to the guidance offered and the person or organisation offering it. Interviews and focus groups with householders, in Burchell’s work and other research, reveal a strong distrust of ‘profit-making’ sources of knowledge (e.g. energy companies).

Box 1.

That’s not to say these two knowledge acquisition practices are mutually exclusive: elements of both can be merged. Some websites now use machine-learning to provide households with tailored energy-savings tips that reflect characteristics of their hour-by-hour energy consumption. People can choose to also provide more information – such as household income and household size – to get more tailored advice. Such combinations allow for higher impact with limited resources, but have lower capacity to provide household-specific solutions.

Generally, says Burchell, while both approaches have promise, energy literacy often fails to deliver the meaningful behavioural change that comes from boosting energy know-how. Yet, for practical and financial reasons, the latter remains underutilised in mainstream policy approaches.

To access Burchell’s full paper, click here.