Across the European Union, thousands of people are getting involved in energy communities (EC) in a bid to move away from big energy providers while saving money and protecting the Planet. But new research suggests that the vulnerable households—who could benefit the most—rarely participate.

“They start a business or cooperative with the idea to jointly invest in renewable energy because either they really want to push the idea of a renewable energy system, or they want to save some costs,” says investigator Florian Hanke. The incentive is that, eventually, “they can produce renewable energy for a lower price [than large electricity suppliers] for their members.”

For Hanke, it seemed obvious that ECs would be an excellent solution for people who would benefit most from lower energy prices, i.e., those struggling to pay energy bills. Instead, he found that he was interacting with two vastly different groups of people, who “hardly come together.”

The individuals who join ECs are usually highly educated, well-paid men, whose “living reality is very different from a lot of energy poor households,” says Hanke.

Additionally, those ECs aware of and wanting to help the energy poor had learned a difficult fact: the inclusive action required is extremely resource-intensive.

“Successfully addressing vulnerable households requires a door-to-door approach. In the end, without enabling a policy framework that supports energy collectives in reaching out to the most vulnerable, inclusive action remains a form of philanthropy often not affordable to energy collectives.”

Florian Hanke

Insights from energy-poor households in Germany

“In Europe, or the Global North, we generally talk about affordability, not so much accessibility because most households have access to energy services,” says Florian Hanke. “It’s a question of whether they can afford them.”

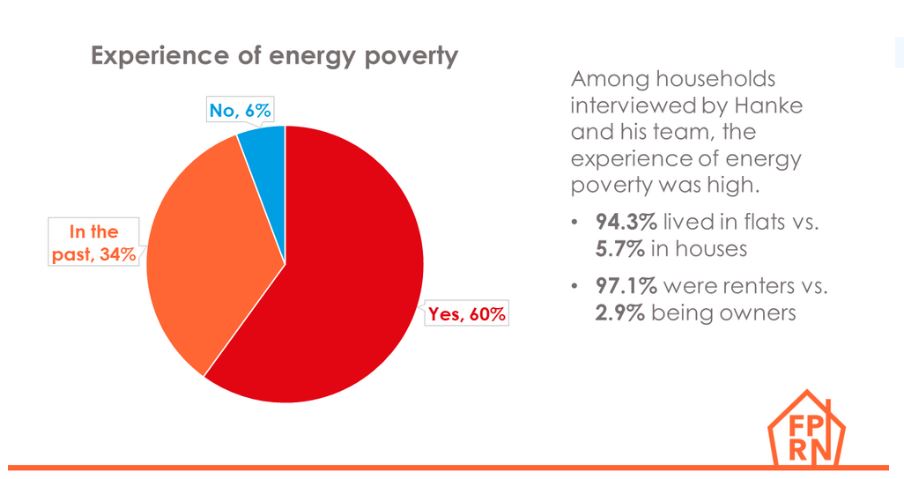

Interviews carried out by Hanke and his team quickly revealed that families in energy poverty are largely unaware that ECs exist, let alone know how to join them.

Many families he spoke to had—at least once—been in situations of having energy suppliers threaten to cut power within two days if they didn’t pay in full. With that kind of pressure, paying the bills to keep the lights on and water running takes precedence over trying to find a long-term, systemic solution for lower cost, cleaner energy.

“It makes it a bit difficult, because in that situation if you want to talk to a household about ECs, it’s about something that is not related to that problem,” says Hanke. “You won’t get their attention; they will only listen to you if you propose to them a way they can quickly and easily pay their bills. You really have to tackle that initial problem first in order to continue talking to them.”

Even so, households interviewed showed that people “want to do their bit of living a sustainable life to protect our environment for future generations,” says Hanke. “The only thing they can really do is change their behaviour to consume as little as possible and that’s what they have already been doing because they are forced to do so.”

Typically, that means switching off the heating or cooling in the hope that they will be able to afford ‘the next’ bill. While they might know the benefits of more efficient appliances, they simply can’t afford to purchase them. Likewise for clean energy technologies, such as solar power panels or a new energy efficient fridge.

The surveys also showed that current efforts to help the energy poor work to a degree. Typically, governments offer quick, one-time fixes, such as energy checks to pay the bills. But even recipients are aware that this does not eliminate the root problem.

What ECs can do that governments can’t (or aren’t)

As noted above, initially, Hanke and his team set out to interview people about how the experience of joining an EC had changed their lives—with a strong focus on households in energy poverty. To date, there is little to suggest that ECs, at least in Germany, are making much difference.

“We’re not really looking at the structural causes of energy poverty at large, and I think there’s so much more we need to do in that respect,” says Hanke. “I would love to continue this conversation and I think at the moment what’s really changing now is that this whole debate is much more public.”

But another important finding emerged from Hanke’s research.

Generally, people interviewed supported the idea of using energy tariffs and taxes to finance systemic change but criticised the additional tax burden for vulnerable groups. As noted in Hanke’s final report, however, German policy makers have still not agreed on how to redistribute CO2 tax revenues, which creates the impression of a particularly burdensome and unfair tax.

ECs have strong potential to step in where government cannot (or have not)—i.e., at the local community level, where people know each other and can more easily help those in need. According to Hanke, getting more ECs involved in energy justice initiatives would require that policy makers develop taxation mechanisms that more fairly distribute costs between large energy investors or suppliers and citizen-led ECs. One such mechanism, he says, would be to use taxes to tap into shareholder profit to better support activities that deliver the value of social welfare.

“ECs adding social welfare would gain access to an enabling policy framework (as demanded by the recast of the EU Renewable Energy Directive) that supplies the needed resources or competitive advantages to enable them to take inclusive action on energy poverty mitigation,” says Hanke.

In short, Hanke has found that a growing number of ECs have ‘the will’ to engage in helping vulnerable households but, at present, finding ‘the way’ is prohibitively difficult.