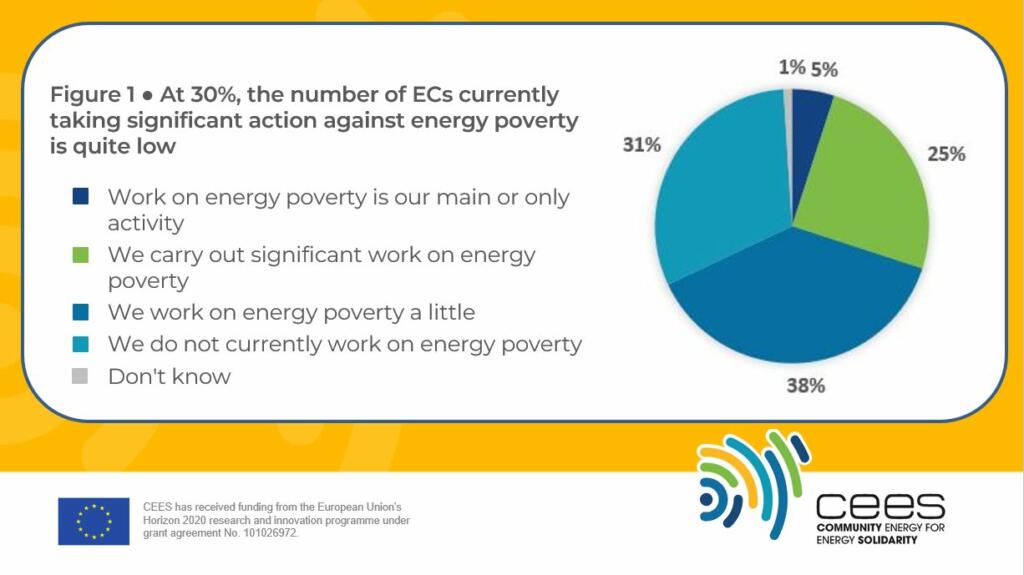

While the majority (57%) of energy communities (ECs) identify energy poverty as a significant or very significant problem in a recent survey, relatively few are taking significant action to tackle it.

Analysis by the University of Birmingham (UoB) of the results of a CEES survey carried out in late 2022 confirms the need for targeted action across several areas for ECs to play the role the European Commission envisions for them in a ‘just, clean energy transition’.

To capture a broad spectrum of ECs working in diverse contexts, the online survey was offered in Croatian, Dutch, English, French, German, Greek, Italian, Polish, Portuguese and Spanish. Seventy seven ECs across 14 European countries gave eligible responses for analysis.

Barriers to engagement with vulnerable households

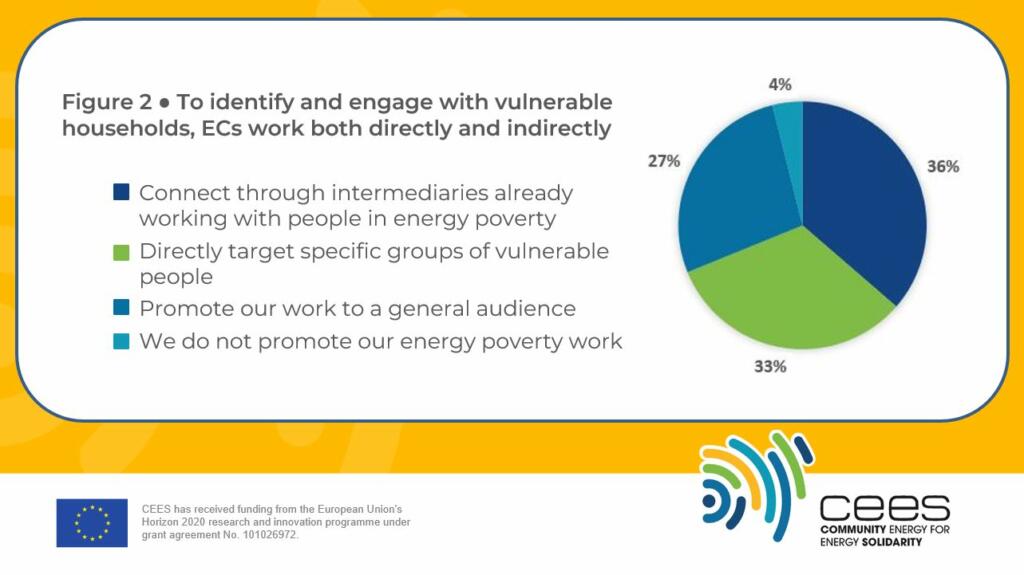

Almost half (48%) of respondents selected ‘lack of householder awareness about the support that is available’ as a challenge to successful engagement with energy vulnerable households, suggesting ECs need to find better ways to communicate with target groups. Several ECs have diverse means of raising awareness of their energy poverty services, including collaborating with other entities (Figure 2).

Two additional major barriers ECs selected reflect characteristics of householders: notably, a lack of capacity to engage (40% of respondents) and reluctance to seek help due to stigma (38%). Language, a lack of confidence within ECs to assess energy poverty, and disability or health issues among householders were also identified as barriers but at lower levels.

Why are so few ECs tackling energy poverty? Barriers to energy poverty action

To better understand what keeps ECs from taking action, the survey allowed participants to select multiple options. For 48 of the ECs analysed, a lack of funding is the main barrier to doing more to tackle energy poverty (77% of responses), followed by a lack of staff (69%) and a lack of knowledge and expertise (48%). A smaller number (21%) identified legislative or regulatory hurdles.

In relation to lack of funding, the public sector was identified as the most important source for 20 of the 50 ECs responding (40%). Several also noted that the short-term nature of grants and high competition for limited funds make it difficult to plan and execute effective, long-term schemes. In turn, lack of funding limits the ability to engage staff. Just 9% (seven of 77) of ECs analysed have more than five full-time employees working on energy poverty, meaning the vast majority have limited capacity.

In a follow-up question on legislative or regulatory considerations, 20 ECs out of 49 respondents said that current frameworks impede their efforts to address energy poverty. Examples include a lack of legislation defining energy poverty; General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) hindering access to vulnerable energy consumers; and policy intermediaries, such as social workers, acting as gatekeepers.

To date, truly transformative interventions are rare

Providing free information and advice is one way ECs tackle energy poverty and help their clients live more comfortably. The most popular topics are recommending behaviour change for energy efficiency (80% of respondents), helping people understand their energy bills (75%) and offering information on renewable energy sources (70%).

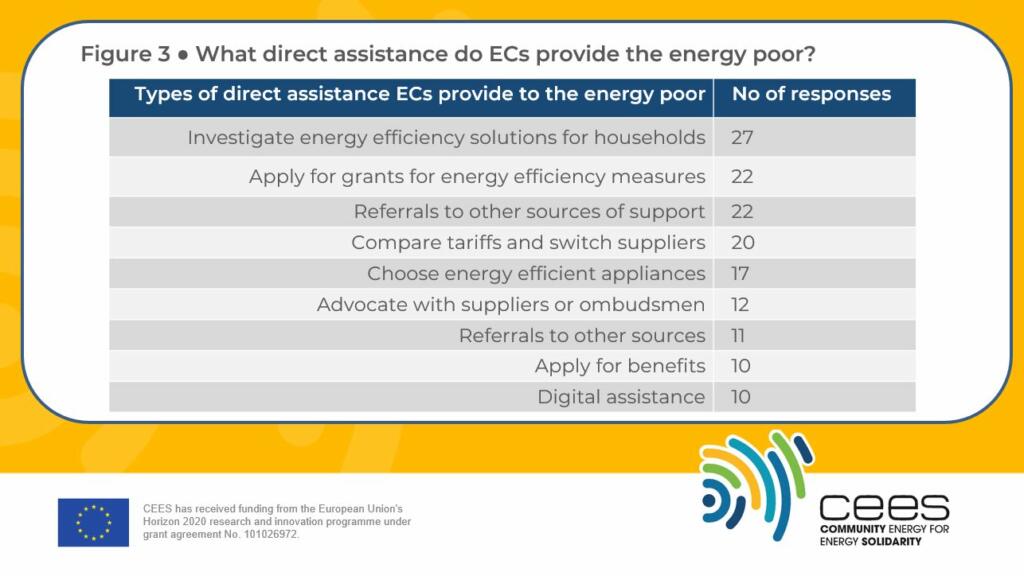

Only 37 ECs answered a question regarding specific interventions they undertake to help reduce energy costs and/or improve energy services to create more comfortable homes (again, they could select multiple options). Of these, the majority (67%) help people implement energy efficiency solutions. More than half (55%) also help households apply for grants for energy efficiency measures and provide referrals to other sources of support with respect to energy poverty (Figure 3).

Only 20 respondents replied to questions related to large-scale interventions – which are most likely to deliver significant benefits to vulnerable households, but typically carry high costs. Installing home-based systems for renewable electricity generation was the most popular approach (65% of respondents). Two ECs fit energy storage devices or batteries and one replaces old boilers with more efficient models. At present, none are installing heat storage devices.

Offering financial assistance may provide temporary relief from energy poverty but is rarely practiced by ECs. Just seven respondents provide financial assistance to clear debts linked to energy consumption, while four use fuel vouchers and two subsidise membership fees. One EC provides grants up to £2 500 (€2 910) to partially cover larger intervention projects. Six ECs provide financial assistance to other organisations to support energy poverty alleviation projects.

What actions can ECs take to tackle energy poverty?

CEES’ mission is to validate EC actions that build energy solidarity and alleviate energy poverty. While all CEES partners are taking action to combat energy poverty in their locality, they face difficulties. ECs would greatly value more supportive legal and regulatory frameworks and increased funding to meaningfully act against energy poverty.